Breadcrumb

- Study with Us

- Focus on Our Trainees

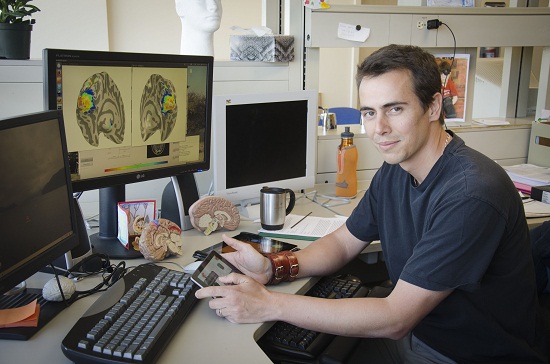

- Simon Clavagnier

Navigation Menu

It was through networking that postdoctoral fellow in neuroscience Simon Clavagnier joined the McGill Vision Research Unit, led by Dr. Robert Hess of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) in 2009. Originally from Lyon, France, he was working on his postdoc in Louvain, Belgium, when he heard that Dr. Hess was looking for a postdoctoral fellow specializing in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transcranial magnetic stimulation.

"In Belgium, I learned the MRI imaging methods used to study the links between vision and cognitive functions like consciousness and movements. Dr. Hess is an authority in the field of amblyopia, a visual impairment also known as lazy eye," says Clavagnier. "He is also someone who is accessible and always enthusiastic. It went well between us immediately."

The young researcher is particularly fascinated by thought and human perception. He did his doctorate in France and Germany in the field of neuropsychology and studied patients with injuries of the cortex suffering from unilateral spatial neglect. These patients behave as if everything that is on the left side of their bodies – be it sound, movement or stimuli of any kind - no longer exists.

"I was interested in the networks of the nervous system and in the relationship between visual information and hand movements in these patients," he says. "When I received the invitation from Dr. Hess to work on amblyopia and return to issues that were not related to injuries, I was very interested."

A game to treat lazy eye

Currently, the team under Dr. Hess is working with the Montreal branch of the French video game developer Ubisoft and with Amblyotech, an American company that develops electronic interface therapies, to create a video game to treat adults with amblyopia.

"In adults, amblyopia is no longer a problem of the eye, but of the brain," explains Clavagnier, who became a research associate in 2011and works at the Montreal general Hospital (MGH) of the MUHC. "Through the game, the brain understands that both eyes are important."

The results are encouraging. Almost 90 per cent of adults tested were able to recover binocular vision, where both eyes are used at the same time. In addition, some of them developed or improved their stereoscopic vision, which enables them to perceive distances. These improvements took place over a six-week training period, and there has been no regression.

"It is gratifying to receive letters from people all over the world with amblyopia who want to try the treatment. But we have to wait for the results of clinical trials underway in adults and children. If they are positive, the game could become recognized as a treatment for amblyopia in about two years."

The partnership between the team at the RI-MUHC, Ubisoft and Amblyotech reflects today's changing context for researchers, says Clavagnier.

"Research is becoming more competitive, and investments increasingly rare. So we have to find an application, develop a project and explain to the business community why it's an interesting idea."

Clavagnier enjoys the outstanding scientific environment and collaborative spirit at the RI-MUHC.

"In Europe, everyone has their turf," he says. "Here, on the other hand, there are many opportunities to learn and talk to students and researchers. They know what they're talking about and will give you time and share equipment or suggest someone who can help you. It enables us to move forward faster and develop other collaborations."